We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

On the Hunt: Southern Resident Killer Whales Hunger for Vanishing Salmon

When Tahlequah—a Southern Resident killer whale who led the news when she carried her dead calf for 17 days in 2018—began carrying another dead calf earlier this year, it was another clue for scientists that these whales are struggling.

A food chain domino effect

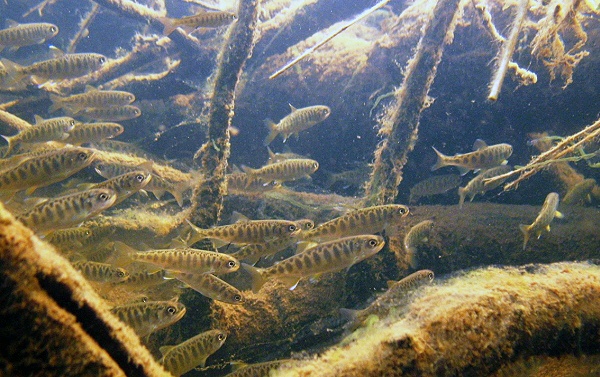

The Southern Resident killer whales are on the brink of extinction with only 73 individuals remaining. These orcas rely heavily on chinook salmon for food, but habitat destruction, overfishing, and environmental changes have drastically reduced salmon populations, leading to malnutrition and increased mortality rates, said Stuart Ellis, a harvest management biologist with the Columbia River Intertribal Fish Commission.

While research shows there are hundreds of factors that are causing the decline of this population of killer whales, scientists say solving the problem of diminished food supply—recovering the once-abundant chinook salmon runs—is the key to turning this trend around.

“We’re talking about an international situation, because these fish also cross international borders.” said Dr. Deborah Giles, of the Columbia River chinook salmon that go all the way to Alaska before returning to their spawning grounds. Giles is Research Director at the nonprofit SeaDoc Society. “Fish born in Washington need to be protected all the way until they get back to their natal river in Washington.”

“While salmon need protection in the ocean, the rivers and their tributaries are at the beginning of this issue. Dams have impacted prey populations of salmon and have had negative impacts on river health where salmon migrate every year,” said Ellis. The four dams on the Lower Snake River produce a portion of the region’s power, but they also cause mortality of smolts migrating downstream and add to the difficulties for fish reaching their spawning grounds.

The population of Southern Resident killer whales peaked at 97 animals in 1996, and declined again to 79 in 2001. Despite 18 births since 2001, the population declined to 73 in 2025. Pollutants, noise, and diminishing food stocks are among the threats to blame for the mortality issues the whales are experiencing.

Salmon are spending less time in the ocean before returning to spawn, resulting in smaller fish, said Ellis.

“The orcas have access to other fish that are not in the same dire straits but it’s fair to say that their food supply continues to be in low abundance and that’s why we have taken some action,” Ellis said.

Threats to orca whales and salmon

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries plays a key role in Southern Resident conservation efforts. NOAA’s recovery plan focuses on increasing prey availability and minimizing human disturbances. “Columbia Basin salmon face a litany of challenges besides the hydro-system, including poor habitat conditions, increasing water temperatures, and lower summer stream flows. Predation by birds and non-native fish as well as sea lions are also an important problem.”

Giles has called for stronger protections against pollution, which not only harms salmon habitats but also leads to toxin accumulation in orcas. She studies orcas by gathering samples of feces. Many of the whales she studies carry dangerously high levels of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and other pollutants, which commonly come from industrial pollution in urban areas, weakening immune systems and reducing reproductive success, she said.

University of Washington Senior Research Scientist Jennifer Tennessen is using advanced technology, such as digital acoustic recording tags, to monitor orca behavior and assess the effects of food scarcity and noise pollution. These tools provide crucial data to shape conservation strategies.

“Research shows that vessel noise forces whales to alter their behavior, expending more energy while foraging. Human activity further exacerbates these issues,” Tennessen said.

Tennessen cited a program in Seattle called Quiet Sound, which encourages boaters to voluntarily slow their vessels to reduce noise for orcas from October to January when they spend time in the area.

“There’s two benefits there. One, you’re less likely to hit a whale when you’re going slower and two, acoustically, the sort of sound structure that your vessel produces isn’t as impactful. Slower vessels aren’t as loud as fast moving vessels,” Tennessen said.

More systemic policy changes and collaborative conservation initiatives are crucial to reversing the decline, Giles said.

“Tahlequah is the poster child showing us in a very visual way that they are not a healthy population,” Giles said, “and we are not doing enough to recover them.”

Kat Harttrup is a whale scientist and Senior in the UW Journalism and Public Interest Communication program who has primarily focused her writing on universal human rights.